'Great Resignation' caused by end of WFH - McKinsey

The pandemic has presented supply chain with many challenges over the past two years, but none as complex and bewildering as the one that is now beginning to face it at scale: the end of working from home (WFH), and the return of people to the office.

It’s like hundreds of millions of us are ending a tour of duty in Afghanistan, and are returning to our home lives. Not my view, but that of US Army veteran Adria Horn, whose take on the end of WFH is sobering, moving, extraordinary and profound. More of that later.

Horn says it is no coincidence that as WFH draws to a close, people are leaving their jobs in their millions - everywhere, including across supply chain functions. ‘The Great Resignation’, people are calling it, and they’re right to.

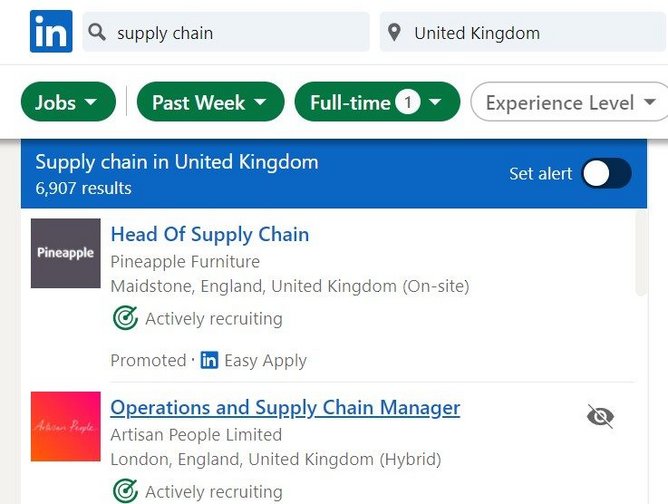

This morning on LinkedIn, I did a broad search for supply chain jobs in the UK, where I am based (see screenshot, top). I set no search parameters on salary, job title or location - only on the date jobs were posted, which I set to the past week. There were 7,980 results. It’s the same everywhere, across the globe.

Great Resignation big problem for supply

So what can businesses do about it? It’s a monumental problem for supply chain because digital transformation is changing it more than at any other point in its history. Cloud-based data-driven supply solutions, fed by AI and IoT, are taking supply into the realms of science fiction, yet such solutions are only as effective as those who marshal them, and if good people keep leaving your company, or don’t want to join, then this is a problem.

People have never been more important to business. Correction: they have always been important, only now it is employees, not employers, who hold all the aces, and they are beginning to play them in spades.

According to McKinsey, healthy organisations excel in three areas: attracting and developing people, investing in helping people reach their goals, and by driving a culture of efficiency and innovation. So there it is. Simple, right? That’s all C-suiters anywhere need know in order to solve the looming employee crisis.

Except of course, nothing is ever simple when it comes to people. Employee retention and attraction is nuanced, multi-faceted and requires an enterprise-wide mindset to be effective. It’s far from simple.

End of WFH ‘like end of a tour of duty’

But at the moment, says Horn, it is very simple. We are all returning from a tour of duty, and our employers must recognise this fact, or face losing us.

Adria Horn is executive VP of workforce at Tilson, a national telecom provider based in Portland, Maine. She was also a serving lieutenant colonel in the US Army Reserve, and served five tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan between 2003 and 2010.

In a new McKinsey report - headlined ‘A military veteran knows why your employees are leaving’ - Horn compares her feelings of returning to the US from deployment in Iraq and Afghanistan to the struggles that employees face today, of returning to the office after years of muddling through the pandemic at home.

“It’s actually a normal response that most people have never gone through,” she says. “I experienced this kind of thing after every return from deployment.”

Covid has left us feeling out of control

She adds: “Coming back from deployment is hard. You’re expecting it to be great, but the biggest feeling is that things are different. The kids are different. Your favourite restaurant closed, your pet died, your softball team broke up. Home isn’t as it was. Your partner bought a new couch while you were away. Things don’t meet your expectations. You seem to have lost control, so your return experience doesn’t feel good at all.”

Horn says the reason so many people are casting around for new jobs right now is because the return to workplace routines will not meet their hopes and expectations in ways they maybe can’t even articulate. “This puts people on edge, throws them off-kilter,” she explains.

She continues: “Since 2001, 1.9 million Americans have been deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. That’s less than 1% of the US population. With Covid, just about everyone in the world was deployed. They didn’t know that they were deployed, and they weren’t equipped to know what was coming, and we still don’t know when or even if it will fully end. With a military deployment at least you have an end date.

Pandemic turned our lives upside down

“Our lives were turned upside down. Many of us lost friends and loved ones, just like in war. People spent their money in crazy ways. They got married, got divorced, made rash decisions - bought motorcycles and maybe crashed them. Some took that bucket-list trip, some ended their own lives.”

“I’m no doctor,” she continues. “I’m no scientist. I’m just a five-time observer of deployment burnout - of the high and lows of returning to normal life, and of that caged feeling that comes with this.”

People, says Horn, are now feeling a need “to set themselves free”.

“The emotional ties that bound us together during the pandemic work period has waned,” she warns.

So what can employers do about all this? After all, like Horn they’re not doctors nor behavioural scientists. They’re just bosses, and colleagues.

Supply bosses ‘need honest talks with staff’

Horn says that at the company she works at, Tilson, “we’ve had a lot of discussion about turnover, and how to reduce it”.

“We quickly came to see that this was a normal, even predictable, reaction,” she adds. “We offer strong mental-health benefits, and during a series of monthly, virtual talks, the COO and I made it clear to our employees that the confusion they might be experiencing is perfectly normal.

“We told them that the things they are feeling are part of a normal process and that it may take them time to process all of it, and feel that they want to stay at Tilson. We told them that this was OK - that if they want to leave we’ll do a professional separation, and that if they want to come back, we’d welcome them back.”

Horn said that some employees did leave, and have subsequently returned.

“Employers should welcome them back,” she urges. “Don’t hold it against your people if they leave suddenly.”

Like kids, supply staff want to feel safe

Horn has one final, powerful, word of advice for bosses who are faced with multiple team members wanting to leave. Treat them as you would your own children.

“I have two children,” she says. “One five years old and the other ten. The five-year-old is full of spit and vigour, just like I was as a kid. A few months ago, she was just giving it to me - mad about this, mad about that. And I was mad right back at her.

“Then I read one of those parenting books, which had a chapter on hugging your angry child. It was exactly the opposite of what I felt like doing. But I started doing it. I started hugging her when she was mad, hugging her hard and long, and things just softened and de-escalated.

“That’s kind of what a lot of employees need now. I’ve never seen it quite like this in all my years at work, but that is what people need now. They need a professional and psychologically safe working environment, which I believe is the equivalent of a long, strong hug.”